16

Kidney Transplant: Eligibility, Surgery, and Long-Term Management

What Is a Kidney Transplant and Why It Matters

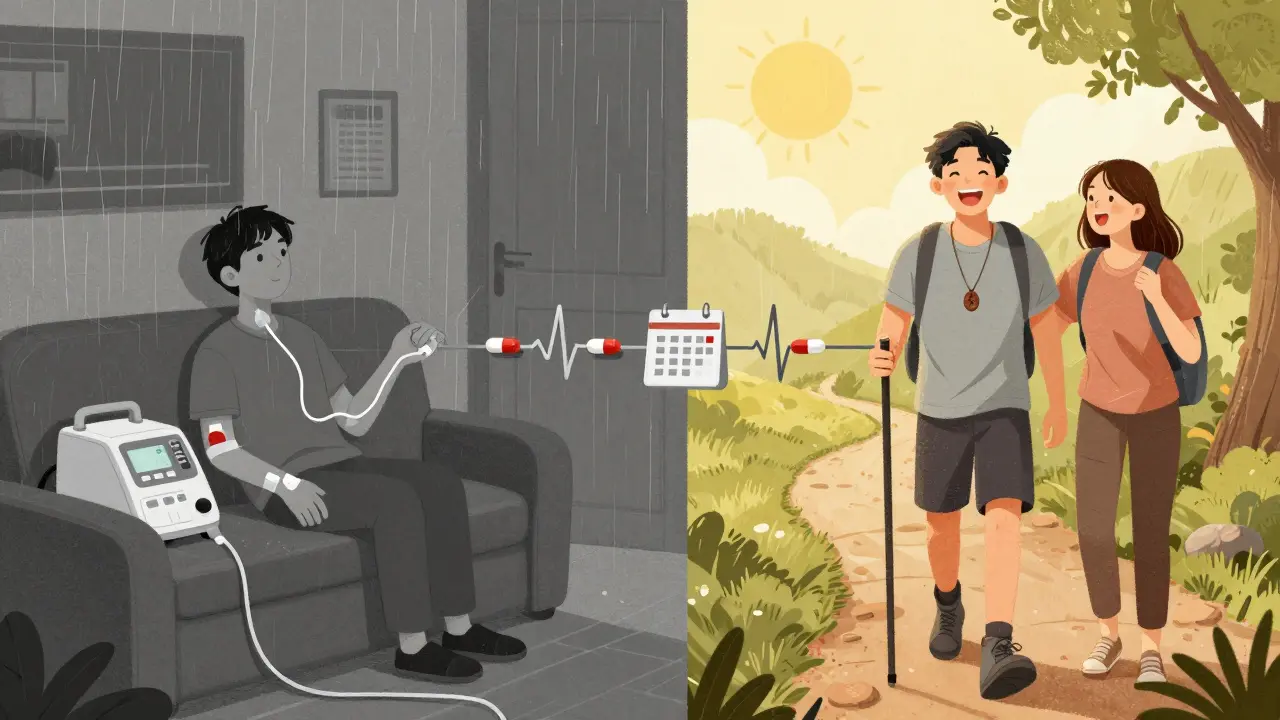

A kidney transplant is when a failing kidney is replaced with a healthy one from a donor. It’s not just a surgery-it’s a life-changing reset for people with end-stage renal disease (ESRD). When your kidneys drop below 15% of normal function, your body can’t filter waste or balance fluids anymore. Dialysis keeps you alive, but it’s exhausting, time-consuming, and doesn’t restore quality of life like a transplant does. People who get a transplant live longer, feel better, and get back to normal activities-working, traveling, playing with grandkids. The 5-year survival rate after a transplant is about 85%, compared to just 50% for those staying on dialysis. That’s not a small difference. It’s the difference between surviving and truly living.

Who Can Get a Kidney Transplant? The Real Eligibility Rules

You can’t just sign up for a transplant. Every transplant center has strict rules, and they’re not just about your kidneys. Your whole body has to be ready. The main requirement is end-stage renal disease, usually defined by a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of 20 mL/min or lower. Some centers, like Mayo Clinic, may consider you if your GFR is up to 25 mL/min-if your kidneys are crashing fast or you already have a living donor lined up.

Age isn’t a hard cutoff. You’re not too old at 70 or even 75 if you’re otherwise healthy. But frailty matters more than your birth certificate. Centers like Vanderbilt check for signs of physical decline: unintentional weight loss, slow walking speed, weak grip, constant tiredness. If you’re frail, your body might not survive the surgery or recovery.

Weight is a big factor too. A BMI over 35 makes you a higher-risk candidate. Over 45? Most centers won’t operate. Why? Fat increases surgical risks-bleeding, infections, longer hospital stays-and it also raises the chance the new kidney will fail. A 2022 study found obese patients had 35% more complications and 20% higher graft failure rates.

Heart and lung health are non-negotiable. If you have severe pulmonary hypertension-systolic pressure above 50 mm Hg at Mayo, or 70 mm Hg at Vanderbilt-you’re not eligible. Same with needing oxygen all the time because of COPD. Your heart needs to pump well, too. Ejection fraction below 35-40%? That’s a red flag. You’ll need a full cardiac workup: echo, stress test, maybe even a heart catheter.

What Disqualifies You? Absolute Contraindications

Some things automatically rule you out. No exceptions.

- Active cancer: If you’re currently being treated for cancer, or if it’s likely to come back after a transplant, you’re not eligible. You usually need to be cancer-free for at least 2-5 years, depending on the type.

- Untreated infections: If you have an ongoing infection like tuberculosis, hepatitis B with active virus, or HIV with low CD4 count or detectable viral load, you’re not a candidate until it’s controlled.

- Substance abuse: Alcohol, opioids, meth-any ongoing use disqualifies you. You need to be clean for at least 6 months, with proof of rehab or counseling.

- Severe mental illness: If you have uncontrolled depression, psychosis, or dementia that makes it impossible to take daily meds, you won’t qualify. This isn’t about stigma-it’s survival. Missing one anti-rejection pill can kill your new kidney.

Transplant centers also check your support system. Do you have someone who can drive you to appointments? Help you remember your pills? Call the doctor if something’s wrong? If you live alone with no backup, your chances drop-even if your body is ready.

The Surgery: What Happens on the Operating Table

The surgery itself takes about 3 to 4 hours. You’re under general anesthesia. The surgeon places the new kidney in your lower belly-not where your old one was. Your own kidneys usually stay in place unless they’re infected, bleeding, or causing high blood pressure.

The new kidney’s blood vessels are stitched to your iliac artery and vein. The ureter (the tube that carries urine) is connected to your bladder. When blood starts flowing, the kidney often starts making urine right away. That’s a good sign. But sometimes, especially with kidneys from deceased donors, it takes a few days to wake up. About 20% of these transplants need temporary dialysis after surgery.

Living donor transplants are faster and smoother. The kidney is fresh, not stored, and the donor’s health is optimized. Deceased donor kidneys can be colder, older, or from someone with health issues. That’s why living donor transplants have a 97% one-year survival rate, compared to 93% for deceased donor ones.

Life After Transplant: The Lifelong Commitment

Getting a new kidney isn’t the end. It’s the start of a new routine. You’ll take immunosuppressants for the rest of your life. These drugs stop your immune system from attacking the new kidney. Common ones include tacrolimus, mycophenolate, and prednisone. Some people get a one-time antibody treatment right after surgery to reduce early rejection risk.

But these drugs come with trade-offs. You’re more likely to get infections, high blood pressure, diabetes, or even certain cancers. You’ll need blood tests every week at first, then monthly, then every 3 months. Annual checkups never stop.

Follow-up visits are strict. Week one: every few days. Week two: weekly. By month three: every two weeks. At six months: monthly. After a year, it’s quarterly. Miss a visit? Your doctor might pull you back into frequent monitoring. Your kidney doesn’t care if you’re busy. It only cares if you take your pills.

Survival rates show why this discipline matters. One-year graft survival: 95% for living donor, 92% for deceased. Five-year survival? 85% for living, 78% for deceased. The difference isn’t magic-it’s adherence. The people who stick to their schedule live longer.

What’s New in Kidney Transplants?

Technology is changing how we match donors and recipients. The Kidney Donor Profile Index (KDPI) scores kidneys from 0 to 100 based on donor age, health, and cause of death. A low KDPI (under 20) means a kidney likely to last 15+ years. A high KDPI (over 85) might only last 5-7 years. But here’s the twist: even high-KDPI kidneys are better than dialysis. A 2022 study showed patients who took these kidneys lived longer and had fewer hospital stays than those who stayed on dialysis.

Researchers are also trying to reduce or eliminate lifelong immunosuppression. Clinical trials at Stanford and the University of Minnesota are testing ways to train the immune system to accept the new kidney without drugs. If it works, it could be a game-changer. But it’s still years away from being standard care.

For now, the best option remains a living donor. A healthy relative or friend giving one kidney is still the gold standard. It’s safer, faster, and lasts longer. And yes, living donation is safe. The donor’s remaining kidney grows slightly to take over full function. Most donors return to normal life within 6 weeks.

What If the Transplant Fails?

Transplants don’t last forever. About 1 in 5 kidneys fail within 5 years. That doesn’t mean you’re out of options. You can go back on dialysis and re-list for another transplant. Many people get a second or even third transplant. The key is staying healthy enough to qualify again. That means controlling blood pressure, staying off tobacco, keeping your weight down, and never skipping meds-even when you feel fine.

Final Thoughts: It’s Not Just About the Kidney

A kidney transplant isn’t a cure. It’s a management plan with a new organ. Success depends on your willingness to change your life. No more skipping pills. No more ignoring high blood pressure. No more drinking alcohol or using drugs. It’s not about being perfect-it’s about being consistent. The people who thrive after transplant aren’t the luckiest. They’re the most disciplined.

If you’re considering a transplant, start early. Talk to your nephrologist. Get evaluated. Find out what’s holding you back-weight, smoking, mental health-and tackle it now. The clock is ticking. Every day on dialysis is a day closer to complications. A transplant isn’t a last resort. It’s the best chance you have to live well again.

Can I get a kidney transplant if I’m over 70?

Yes, age alone doesn’t disqualify you. Transplant centers like UCLA don’t set an upper age limit. Instead, they assess your overall health, heart function, frailty, and ability to recover. If you’re physically strong, mentally clear, and have good support, you can be a candidate-even in your 70s or 80s.

What if I have diabetes or high blood pressure?

Having diabetes or high blood pressure doesn’t automatically rule you out-but they must be well-controlled. Poor control increases the risk of damaging the new kidney. You’ll need stable HbA1c levels (under 7.5%) and blood pressure under 140/90. Your team will work with you to get there before listing.

How long is the wait for a deceased donor kidney?

In the U.S., the average wait is 3 to 5 years, but it varies by region, blood type, and how sensitized your immune system is. People with rare blood types or high antibody levels may wait over 10 years. Having a living donor can cut that wait to zero.

Can I drink alcohol after a kidney transplant?

Moderate alcohol is usually allowed-no more than one drink per day for women, two for men. But heavy drinking is dangerous. It harms the liver, raises blood pressure, and can interact with immunosuppressants. Many transplant centers recommend avoiding alcohol entirely, especially in the first year.

Do I need to follow a special diet after a transplant?

Yes, but it’s less strict than on dialysis. You’ll need to limit salt to control blood pressure, watch potassium and phosphorus if your levels are high, and avoid grapefruit (it interferes with some meds). A low-fat, balanced diet helps manage weight and diabetes risk. A dietitian will help you adjust your plan based on your medications and lab results.

Can I get pregnant after a kidney transplant?

Yes, many women have healthy pregnancies after transplant-but only after waiting at least 1 year and if kidney function is stable. Your immunosuppressants may need adjustment. You’ll need close monitoring by a high-risk OB and your transplant team. Most babies are born healthy, but premature birth and low birth weight are more common.

Kasey Summerer

January 18, 2026 AT 02:59Cheryl Griffith

January 19, 2026 AT 01:28swarnima singh

January 19, 2026 AT 13:51Isabella Reid

January 20, 2026 AT 17:11Jody Fahrenkrug

January 22, 2026 AT 00:50Allen Davidson

January 23, 2026 AT 09:49Corey Sawchuk

January 24, 2026 AT 23:08Christina Bilotti

January 25, 2026 AT 15:17vivek kumar

January 25, 2026 AT 20:48Riya Katyal

January 26, 2026 AT 02:05Henry Ip

January 26, 2026 AT 02:35waneta rozwan

January 27, 2026 AT 01:33kanchan tiwari

January 28, 2026 AT 21:25Bobbi-Marie Nova

January 30, 2026 AT 07:11Nicholas Gabriel

January 31, 2026 AT 22:58