H. pylori infection: what it is and why it matters

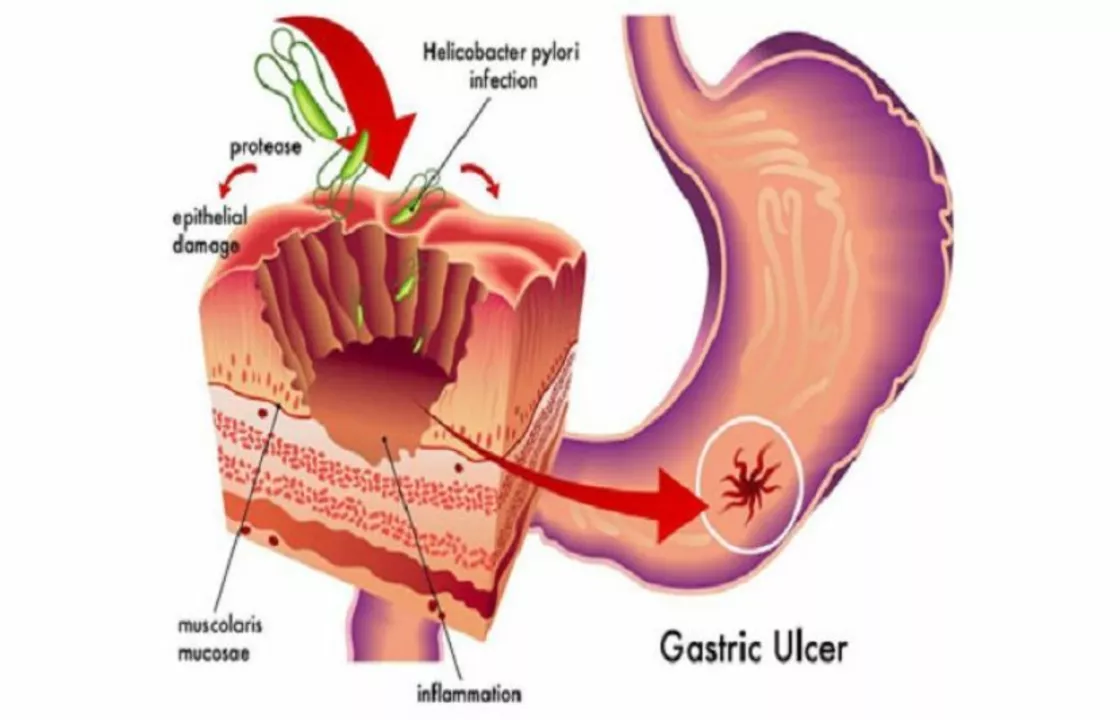

H. pylori is a bacterium that lives in the stomach lining and infects a lot of people worldwide — many don’t even know they have it. When it causes trouble, you may get long-lasting stomach pain, bloating, nausea, or peptic ulcers. Left untreated, H. pylori can raise the risk of more serious issues like bleeding ulcers and, over many years, an increased risk of stomach cancer.

How you’ll know — common symptoms and smart warning signs

Many people have no symptoms. When symptoms do show up, they usually include dull or burning pain in the upper belly, frequent burping, feeling full quickly, and sometimes nausea. Watch for red flags: black or bloody stool, vomiting blood, sudden severe pain, unexplained weight loss, or fainting. Those signs need urgent medical attention.

If you have persistent stomach pain or a history of ulcers, your doctor may test you for H. pylori. Don’t ignore ongoing symptoms—early testing helps prevent complications and guides proper treatment.

Testing, treatment, and practical tips

Diagnosis is usually simple. Noninvasive tests include the urea breath test and stool antigen test; both are reliable. Blood antibody tests are less useful because they can stay positive after the infection is gone. If you have severe symptoms, an endoscopy with a biopsy may be done.

Treatment typically combines a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) to lower acid plus two or three antibiotics taken for 10–14 days. Because antibiotic resistance is rising, doctors choose regimens based on local resistance patterns and your previous antibiotic use. Finish the full course exactly as prescribed — stopping early makes resistance and treatment failure more likely.

After treatment, a test of cure is recommended using a breath or stool test four weeks after finishing antibiotics and after stopping PPIs for two weeks. This confirms the infection is gone and avoids unnecessary repeat treatments.

Small extra steps help: avoid NSAIDs if you have an active ulcer, tell your doctor about past antibiotic use, and consider a probiotic to reduce some antibiotic side effects (ask your provider first).

Prevention focuses on hygiene: wash hands well, drink safe water, avoid sharing eating utensils in places with poor sanitation, and choose well-cooked food. These steps lower the chance of catching H. pylori, which spreads mainly by oral-oral or fecal-oral routes.

If you suspect H. pylori or have persistent stomach problems, see your doctor. Getting tested and treated when needed can relieve symptoms fast and reduce long-term risks to your stomach.

30

The Connection between Epigastric Pain and H. Pylori Infection

In my latest blog post, I explored the connection between epigastric pain and H. Pylori infection. Epigastric pain, which is the discomfort felt in the upper abdomen, can sometimes be linked to H. Pylori, a type of bacteria that can cause stomach ulcers. I discovered that this bacteria can also lead to gastritis, which may further contribute to the sensation of pain in the epigastric region. It's important to get tested for H. Pylori if you're experiencing persistent epigastric pain, as early detection and treatment can help prevent complications. Stay tuned for my next post, where I'll discuss treatment options and ways to prevent H. Pylori infection.

Latest Posts

Popular Posts

-

OTC Heartburn Medications: Antacids, H2 Blockers & PPIs Explained

OTC Heartburn Medications: Antacids, H2 Blockers & PPIs Explained

-

Enteral Feeding Tube Medication Safety: Compatibility and Flushing Protocols Explained

Enteral Feeding Tube Medication Safety: Compatibility and Flushing Protocols Explained

-

Magnesium Supplements and Osteoporosis Medications: What You Need to Know About Timing

Magnesium Supplements and Osteoporosis Medications: What You Need to Know About Timing

-

Extended Use Dates: How the FDA Extends Drug Expiration Dates During Shortages

Extended Use Dates: How the FDA Extends Drug Expiration Dates During Shortages

-

Meniere’s Diet: How Sodium Restriction and Fluid Balance Reduce Vertigo and Hearing Loss

Meniere’s Diet: How Sodium Restriction and Fluid Balance Reduce Vertigo and Hearing Loss