17

How Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Leads to Anemia

CLL Anemia Type Predictor

This tool helps identify the most likely cause of anemia in CLL patients using key clinical and laboratory indicators from the article. Results are based on evidence-based diagnostic criteria.

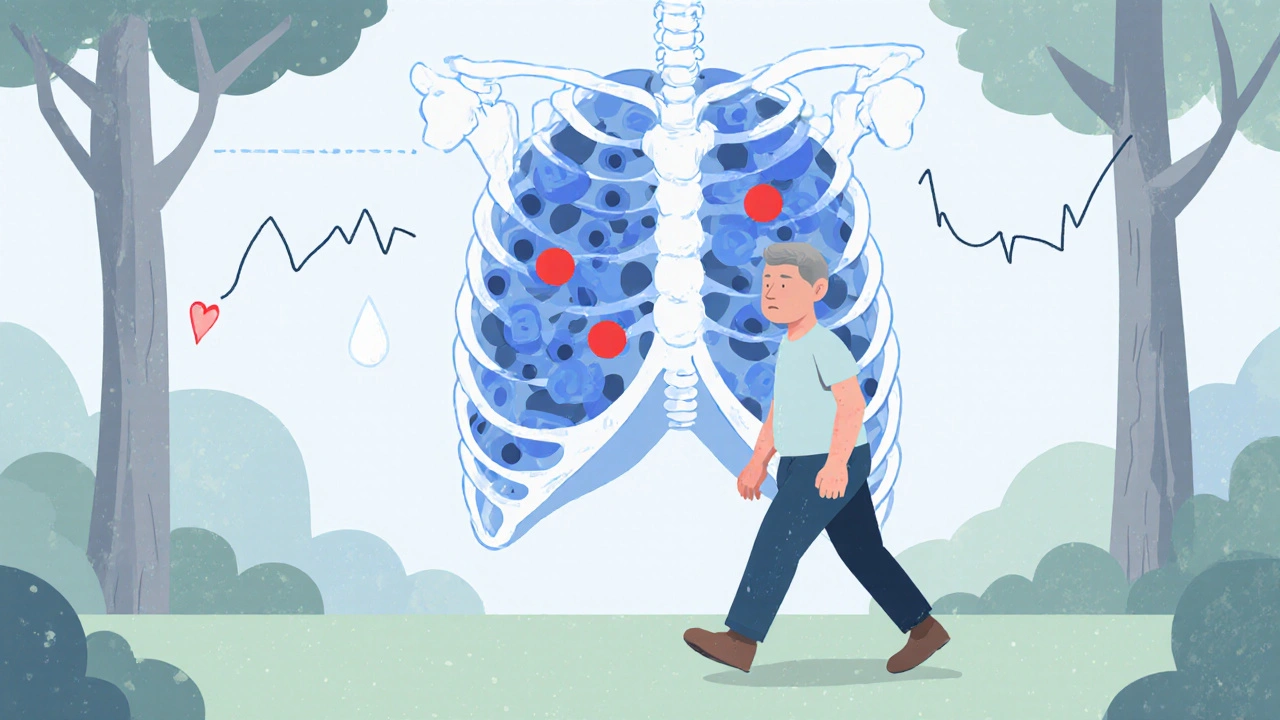

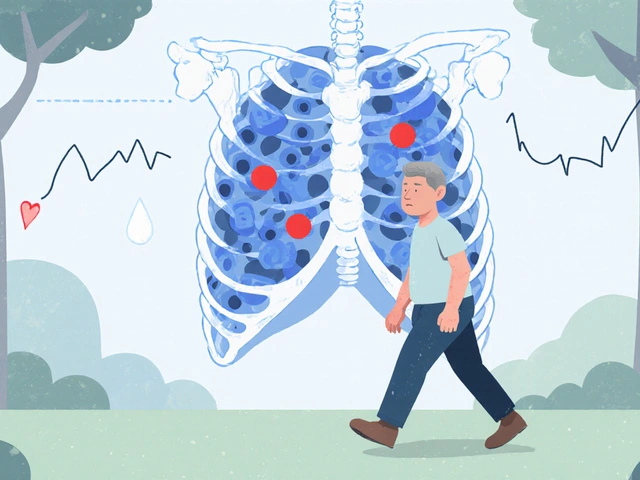

Imagine being told you have a blood cancer and then noticing that even a short walk leaves you winded. That extra fatigue is often a sign of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL), a slow‑growing cancer of B‑cell lymphocytes that crowd the bone marrow and blood.

What is Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia?

Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia is the most common leukemia in adults in the United States. It typically appears after the age of 60, progresses over years, and often stays asymptomatic until it interferes with normal blood‑forming processes. Key characteristics include:

- Elevated white‑blood‑cell count dominated by mature‑looking but functionally defective B‑lymphocytes.

- Bone‑marrow infiltration that squeezes out normal progenitor cells.

- Frequent lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly.

Because CLL originates in the immune system, it can trigger a cascade of secondary problems - anemia being one of the most common.

What is Anemia?

Anemia describes a condition where the blood lacks enough healthy red blood cells (RBCs) or hemoglobin to deliver adequate oxygen to tissues. Symptoms range from mild fatigue to severe shortness of breath, dizziness, and pallor. Anemia isn’t a single disease; it’s a spectrum of disorders with distinct causes, laboratory findings, and treatments.

Why Do CLL and Anemia Often Appear Together?

The link isn’t accidental. Several biological mechanisms connect the two:

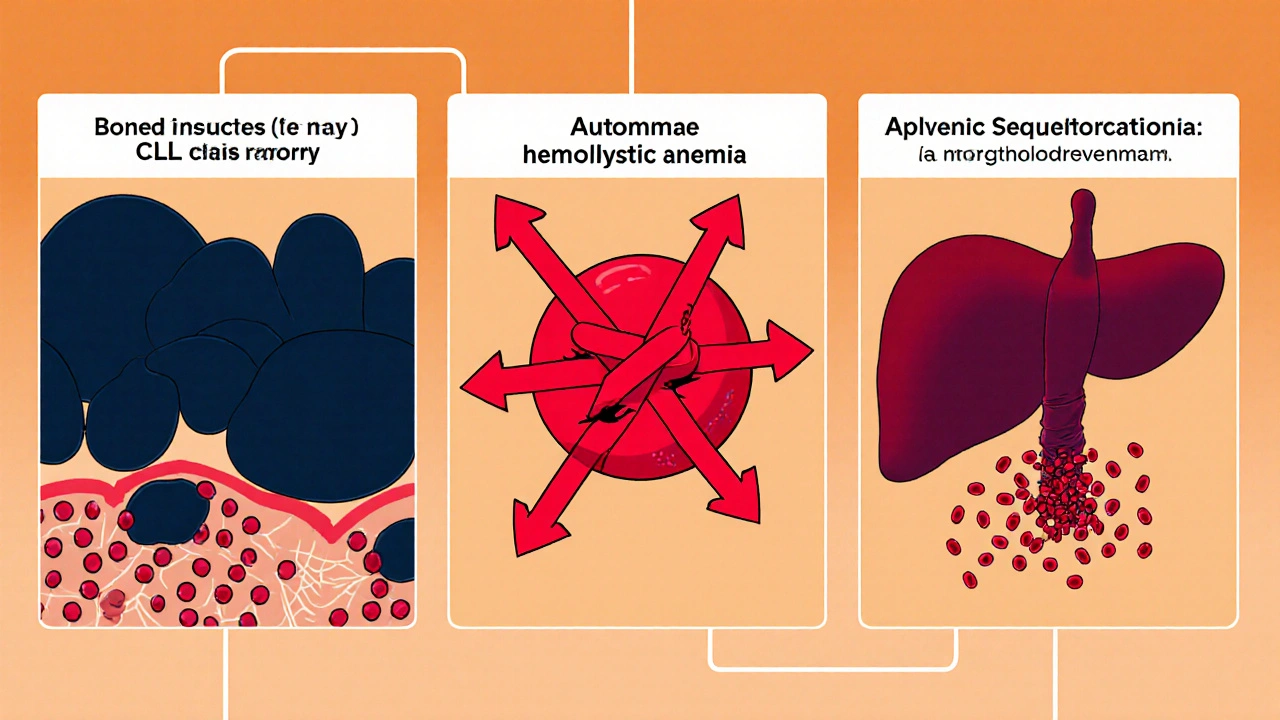

- Bone‑marrow crowding. CLL cells proliferate inside the marrow, reducing space for erythroid precursors. The result is a production‑side shortage of RBCs.

- Autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA). In up to 10% of CLL patients, the immune system creates antibodies that mistakenly destroy red cells, leading to rapid hemolysis.

- Anemia of chronic disease (ACD). Persistent inflammation from CLL raises cytokines like IL‑6, which block iron release and blunt erythropoietin response.

- Treatment‑related effects. Chemotherapy (e.g., fludarabine) and targeted agents (e.g., ibrutinib) can suppress bone‑marrow function or cause hemolysis.

- Spleen sequestration. Enlarged spleen (splenomegaly) can trap and destroy RBCs, adding another loss pathway.

Types of Anemia Most Common in CLL

| Feature | Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia (AIHA) | Anemia of Chronic Disease (ACD) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary cause | Antibody‑mediated RBC destruction | Inflammation‑driven iron sequestration |

| Lab hallmark | Positive Direct Coombs test, ↑LDH, ↓haptoglobin | Low serum iron, high ferritin, normal/low transferrin |

| Reticulocyte count | Elevated (bone‑marrow compensation) | Low or normal (production suppressed) |

| Treatment focus | Immunosuppression (steroids, rituximab), avoid triggers | Control underlying CLL, address inflammation, consider erythropoiesis‑stimulating agents |

How Doctors Diagnose the CLL‑Anemia Connection

Diagnosing anemia in a CLL patient isn’t a single test; it’s a stepwise process:

- Complete blood count (CBC) - looks for low hemoglobin, low hematocrit, and evaluates mean corpuscular volume (MCV).

- Peripheral smear - checks for spherocytes, schistocytes (signs of hemolysis) or abnormal lymphocytes.

- Reticulocyte count - distinguishes production‑vs‑destruction causes.

- Direct antiglobulin (Coombs) test - confirms AIHA.

- Serum iron studies (iron, ferritin, total iron‑binding capacity) - helps identify ACD.

- Bone‑marrow biopsy (rarely needed) - assesses marrow cellularity when production failure is suspected.

Imaging (ultrasound or CT) may be ordered to evaluate splenomegaly, which can contribute to sequestration.

Management Strategies Tailored to the Underlying Cause

Effective treatment hinges on knowing why the anemia exists.

When AIHA Is the Culprit

- First‑line steroids. Prednisone 1mg/kg daily often raises hemoglobin within weeks.

- Rituximab. An anti‑CD20 monoclonal antibody that depletes the antibody‑producing B‑cells, useful for steroid‑refractory AIHA.

- Splenectomy. Reserved for persistent hemolysis when medical therapy fails.

When Anemia of Chronic Disease Dominates

- Control CLL activity - targeted agents like ibrutinib or venetoclax often improve anemia by reducing inflammatory cytokine load.

- Iron supplementation is usually ineffective unless iron‑deficiency coexists.

- Erythropoiesis‑stimulating agents (ESA) can be considered, but only after CLL is under control.

When Treatment‑Induced Anemia Occurs

- Growth‑factor support - G‑CSF for neutropenia, but for RBCs, ESA may be used cautiously.

- Dose adjustments or drug holidays - especially with fludarabine‑based regimens.

- Transfusion support - packed red cells for symptomatic severe anemia.

Living with Both Conditions: Practical Tips

- Track symptoms daily - fatigue levels, shortness of breath, and any new bruising.

- Maintain a balanced diet rich in folate, vitaminB12, and iron (if not contraindicated).

- Stay hydrated; dehydration can exacerbate hemolysis.

- Discuss vaccination status - splenectomy patients need pneumococcal, meningococcal, and Haemophilus influenzae vaccines.

- Engage in moderate exercise - improves circulation and can lessen fatigue without overtaxing the marrow.

Future Directions and Research

Newer targeted therapies such as BTK inhibitors (ibrutinib, acalabrutinib) and BCL‑2 antagonists (venetoclax) are reshaping CLL treatment. Early data suggest they cause less marrow suppression and lower rates of AIHA compared with traditional chemoimmunotherapy. Ongoing trials are also evaluating prophylactic low‑dose steroids to prevent AIHA in high‑risk patients.

Bottom Line

When CLL and anemia appear together, it’s usually a signal that the disease is affecting blood production, immune regulation, or both. Pinpointing the exact mechanism-whether marrow crowding, autoimmune destruction, chronic inflammation, or treatment side‑effects-guides the right therapy and helps patients keep their energy levels up.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why does CLL cause fatigue even before anemia develops?

CLL cells release cytokines that create a chronic inflammatory state. This inflammation can impair muscle metabolism and reduce oxygen utilization, leading to fatigue before the blood count actually drops.

Can I prevent autoimmune hemolytic anemia if I have CLL?

There’s no guaranteed prevention, but keeping CLL under control with modern targeted agents lowers the risk. Some doctors also monitor Coombs tests regularly in high‑risk patients.

Is iron supplementation safe for CLL‑related anemia?

Only if iron‑deficiency is confirmed. Most CLL‑related anemia is due to AIHA or chronic disease, where extra iron won’t help and could even cause harm.

How often should I have blood work to monitor anemia?

During active treatment, a CBC every 2‑4weeks is typical. In stable remission, every 3‑6months is usually sufficient, but your doctor may adjust based on symptoms.

Can blood transfusions cure anemia in CLL?

Transfusions raise hemoglobin quickly and relieve symptoms, but they don’t treat the underlying cause. They’re used for severe or symptomatic anemia while definitive therapy addresses the root issue.

Valerie Vanderghote

October 17, 2025 AT 01:48Living with CLL and the shadow of anemia can feel like trudging through an endless fog, each breath a reminder that the marrow is a battlefield where the invaders have taken up residence, and the healthy cells are forced into hiding. The chronic fatigue that settles in the bones is not just a symptom but a story of cytokines whispering sabotage into muscle fibers, draining the vigor before the lab results even catch up. One day you could be strolling down the hallway of a clinic, notebook in hand, trying to recall the last time you felt truly energetic, and the next you’re on the couch, wondering if the world has become a blur of white lab coats. It isn’t just the physiological strain; the emotional weight of watching your blood counts swing like a pendulum adds a layer of anxiety that can be harder to quantify. Every new symptom feels like a personal betrayal, a reminder that the disease is not merely a set of numbers but an ever‑present companion that can turn the simplest tasks into Herculean efforts. When the marrow is crowded, the body’s natural response is to compensate, producing more immature cells that often lack the robustness needed for proper oxygen transport, leaving you perpetually short of breath. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia adds another twist, as the immune system, already confused by the cancer’s presence, decides to turn on the very red cells that are trying to survive, creating a paradox where your body fights itself. The inflammation from chronic disease acts like a thick curtain, blocking iron’s release and muffling the production signals, further compounding the anemia. Even the treatments, designed to fight the cancer, can sometimes knock the wind out of the supply chain, making the management of anemia a moving target. The splenomegaly that drags the spleen into a larger size becomes a hidden sink, capturing red cells and holding them hostage, contributing to the overall decline. Yet, within this storm, there are glimmers of hope: targeted therapies that spare the marrow, the occasional rise in hemoglobin that feels like a sunrise after a long night. It is essential to keep a meticulous symptom diary, noting each instance of breathlessness or dizzy spell, as these details become the breadcrumbs leading physicians to the root cause. Nutrition plays a role too; a diet rich in folate and B12 can support erythropoiesis, though it is not a panacea for the complex mechanisms at play. Regular blood work, perhaps every few weeks, becomes the rhythm of life, a metronome marking progress or warning of setbacks. Ultimately, understanding that anemia in CLL is a multifactorial villain allows patients and doctors to craft a tailored approach, blending medication, lifestyle adjustments, and vigilant monitoring to keep the blood flowing and the spirit buoyed.

Michael Dalrymple

October 22, 2025 AT 20:41It's essential to remember that the interplay between CLL and anemia is a dynamic process, and a systematic approach to diagnosis can illuminate the underlying cause. By evaluating CBC trends alongside reticulocyte counts and Coombs testing, clinicians can differentiate between production failure and hemolysis. Tailoring therapy-whether it be steroids for AIHA or targeted agents to mitigate chronic inflammation-optimizes patient outcomes while preserving quality of life. Moreover, patient education on symptom monitoring empowers individuals to participate actively in their care plan.

Richard O'Callaghan

October 28, 2025 AT 14:34I cant help but llike to point out that when you are sitted in the doc's office and they talk about "bone marrow crowding" I actually start remembering the times I tried to fit too many boxes in my cubicle and it felt kinda the same, like "oh no these cells are just everywhere". It also makes me think about how the diet can be thinked about, maybe some iron or folate but only if they test it. The whole autoimmune hemolysis thing, it kinda feels like your own immune system getting a little too dramatic about the red blood cells, like a soap opera. Anyway, just my two cents, hope it helps.

Alexis Howard

November 3, 2025 AT 09:28Honestly the anemia in CLL is just overblown.

Steve Holmes

November 9, 2025 AT 04:21Wow, great breakdown, kudos! I especially appreciate the reminder about keeping a daily symptom log, because tracking fatigue, shortness of breath, and even subtle bruising can really help the doc spot a trend, and not just a one‑off value. Also, the point on balanced diet-folate, B12, iron (when appropriate)-is spot on; I always tell patients to aim for leafy greens, beans, and fortified cereals, but to double‑check iron labs first. Lastly, never underestimate the power of staying active; moderate exercise can boost circulation without taxing the marrow, which is a win‑win.

Tom Green

November 14, 2025 AT 23:14Thanks for sharing that comprehensive view, it’s a solid foundation to build on. From a mentorship perspective, I’d add that patients should also be encouraged to discuss any new medications or supplements with their oncology team, as these can sometimes interact with the disease process. Additionally, while maintaining a balanced diet is vital, it’s equally important to avoid excessive iron supplementation unless iron‑deficiency is clearly documented, because that could fuel unwanted oxidative stress. Lastly, remind folks that emotional support-whether through counseling or community groups-can play a crucial role in coping with the chronic nature of CLL and its related anemia.

Frank Diaz

November 20, 2025 AT 18:08The philosophical underpinning of CLL‑induced anemia reveals a deeper truth: the body, when besieged, becomes a theatre of paradox, where the immune system both protects and betrays. One must contemplate the irony of a disease that simultaneously inflames and starves the marrow of iron, a duality that challenges our simplistic notions of causality. In this light, therapeutic interventions become not just medical acts but moral choices, aiming to restore balance in a system tipped toward self‑destruction.

Russell Abelido

November 26, 2025 AT 13:01Reading all these insights really hits home. I feel you, friend-dealing with the constant fatigue can feel like walking through a fog that never lifts. The point about staying hydrated especially resonated with me, because even a subtle drop in fluid can make hemolysis feel more intense. Keep your chin up; you’re not alone in this battle, and the community here is ready to rally behind you! :)

lisa howard

December 2, 2025 AT 07:54Oh dear, let me paint the scene for you: the moment the doctor mentions "autoimmune hemolytic anemia" feels like a curtain ripping away, revealing a storm of red cells clashing with misguided antibodies, a drama of self‑destruction enacting right before your eyes. The marrow, once a bustling factory, now resembles a cramped subway car during rush hour, with CLL cells elbowing out every hopeful erythroblast. And then there’s the spleen-oh, that mischievous organ-expanding like a balloon, trapping those poor reds, as if it were a tax collector grabbing every coin. The fatigue, you ask? It’s the quiet whisper of the body screaming, a lament that the oxygen delivery system is sabotaged from within. My own experience taught me that every short walk feels like climbing a mountain, each breath a reminder that the blood, once a river, now runs shallow. Yet, amidst this chaos, there’s a silver lining: the very treatments that silence the CLL can, in their grace, let the marrow breathe again. So, I urge you-don’t let the drama consume you; instead, become the director of your own story, wielding knowledge and hope as your stage props.

Cindy Thomas

December 8, 2025 AT 02:48Let’s set the record straight: the mechanisms behind CLL‑related anemia are not some mystical mystery, they’re well‑documented pathways that you can actually learn. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia involves antibodies that, frankly, you could test for with a simple Coombs; chronic disease anemia is driven by IL‑6, which you can measure and address; and marrow infiltration is visible on a biopsy, no crystal ball needed. So before you start guessing, just look at the labs, and you’ll see the answer. 😊

Kate Marr

December 13, 2025 AT 21:41Patriots, listen up! The fight against CLL‑related anemia is a battle for our great nation’s health, and we must support those on the front lines. 🩸💪🇺🇸 Let’s champion research, fund innovative therapies, and ensure every patient gets the best care possible. Together we stand, together we heal!

James Falcone

December 19, 2025 AT 16:34Our country's resilience shines bright when we back cutting‑edge CLL treatments that spare the marrow – that's the American way.

Sara Werb

December 25, 2025 AT 11:28Wow, the mainstream narrative about CLL‑induced anemia is a total distraction, folks! Everyone talks about cytokines and marrow infiltration, but what about the hidden toxins that are being quietly pumped into the bloodstream by the very labs we trust? Think about the way pharmaceutical giants funnel money into “research” that keeps us in a loop of dependency. This is not a coincidence, it’s a carefully orchestrated campaign to keep the population weak and compliant. The splenomegaly you hear about? Possibly a symptom of an environmental exposure we’re never told about. Stay vigilant, question the data, and never accept the official story at face value! ☝️

Winston Bar

December 31, 2025 AT 06:21Honestly, reading through all this feels like an endless lecture-yeah, anemia’s a problem, we get it. The whole “track your symptoms” thing is just more paperwork for busy patients. And the “targeted therapies are better” line? Overhyped. People need to stop glorifying every new drug like it’s a miracle.