6

Pharmacy Reimbursement: How Generic Substitution Impacts Pharmacies and Patients Financially

When a pharmacist hands you a prescription for a generic drug instead of the brand-name version, it’s not just a simple swap. Behind that decision lies a complex financial system that determines how much the pharmacy gets paid, how much you pay at the counter, and who makes the real profit. In 2025, over 90% of prescriptions filled in the U.S. are for generic drugs. That’s up from just 33% in 1993. But the financial incentives driving this shift aren’t always aligned with what’s best for patients or pharmacies.

How Pharmacies Get Paid for Generic Drugs

Pharmacies don’t get paid the same way for every drug. For brand-name medications, reimbursement is often based on the Average Wholesale Price (AWP), minus a set percentage. But for generics, it’s a different story. Most payers - including Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurers - use something called a Maximum Allowable Cost (MAC) list. This is a list of the highest price a pharmacy will be reimbursed for each generic drug, regardless of what the pharmacy actually paid for it.

Here’s the catch: MAC lists aren’t standardized. One PBM might set the MAC for a 30-day supply of lisinopril at $4.50, while another sets it at $8.20. The pharmacy might have bought it for $2.10. If the MAC is $8.20, the pharmacy pockets $6.10 - minus the dispensing fee. But if the MAC drops to $4.50, the pharmacy only makes $2.40. That’s a huge swing in profit on a single prescription.

Some pharmacies operate on a cost-plus model, where they’re paid a fixed percentage above what they paid for the drug. That sounds fair, right? But many PBMs have moved away from it because it doesn’t let them control costs as tightly. Cost-plus gives pharmacies more predictable margins, but it also limits the ability of PBMs to profit from price differences.

The Hidden Profit in Generic Substitution

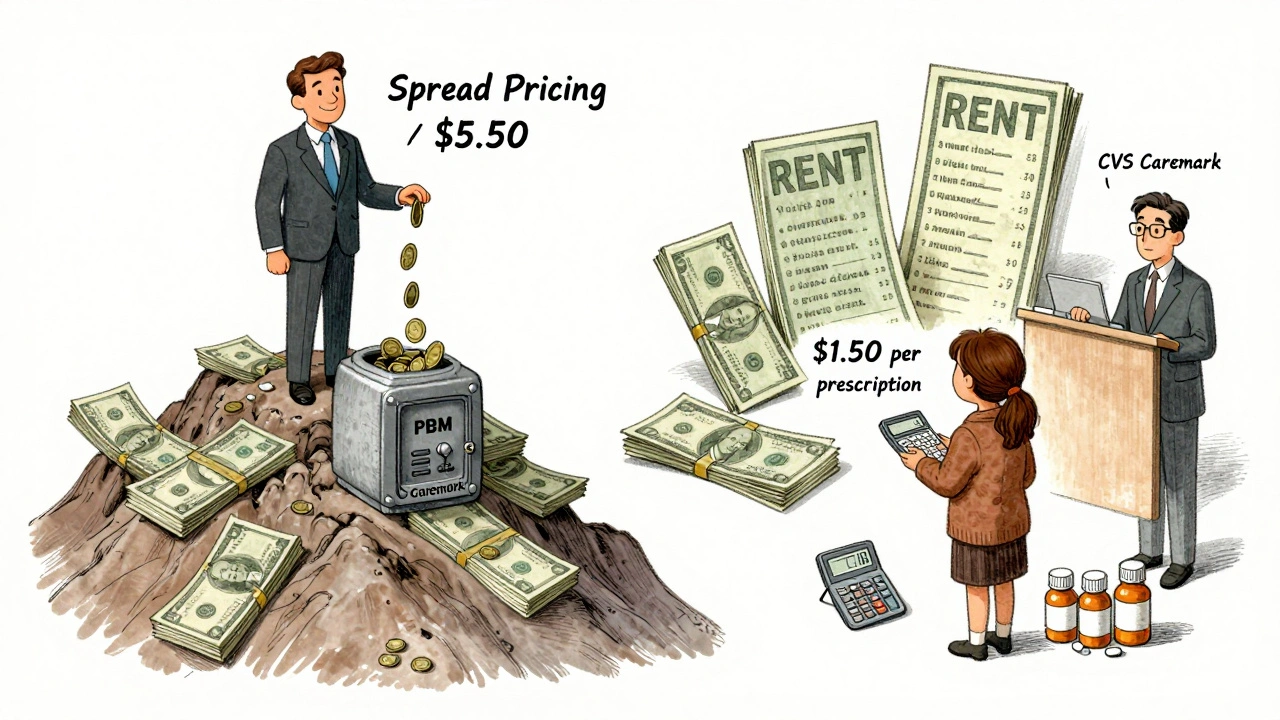

Generic drugs have a gross margin of about 42.7%, compared to just 3.5% for brand-name drugs. That’s why pharmacies are eager to dispense them. But here’s where things get twisted: PBMs don’t always want the cheapest generic. They want the one that gives them the biggest spread.

Spread pricing is when a PBM negotiates a low acquisition cost with the pharmacy - say $1.50 for a generic - but charges the insurer $7.00. The $5.50 difference is the spread. And PBMs make more profit when the MAC list includes higher-priced generics, even if cheaper, equally effective alternatives exist. Studies show that some generics substituted for the same drug class had prices 20 times higher than their therapeutic alternatives. And the pharmacy? They get paid the MAC amount, so they don’t care which one it is - as long as they get reimbursed.

Patients don’t see this. They pay their copay - often a flat $10 or $15 - no matter how much the drug actually costs. So if the PBM sets a high MAC, the patient pays the same, but the system wastes money. That money doesn’t go to the pharmacy. It goes to the PBM.

Therapeutic Substitution: The Bigger Savings Opportunity

Most people think generic substitution means swapping one brand for its generic version. But there’s a bigger opportunity: therapeutic substitution. That’s when a pharmacist or PBM switches a patient from a brand-name drug to a different generic drug in the same class - say, switching from a brand-name statin to a different generic statin that’s cheaper.

The Congressional Budget Office found that in 2007, switching single-source brand-name drugs to generic alternatives saved $4 billion. But swapping one generic for another generic? Only $900 million. Why? Because the biggest savings come from replacing expensive branded drugs - not from swapping between generics.

Yet most reimbursement systems still focus on generic substitution, not therapeutic substitution. PBMs don’t incentivize pharmacists to suggest cheaper alternatives in the same class. Why? Because those alternatives aren’t always on the formulary. And if they’re not on the formulary, they don’t get reimbursed.

Why Independent Pharmacies Are Struggling

Over 3,000 independent pharmacies closed between 2018 and 2022. Why? Because reimbursement rates have been squeezed. The average dispensing fee - the flat fee pharmacies get for filling a prescription - has barely budged in 15 years, hovering around $4 to $6. Meanwhile, the cost of running a pharmacy - rent, staff, compliance, technology - has gone up.

For a small pharmacy, a single generic prescription might only net $1.50 after paying for the drug and labor. That’s not sustainable. Many now rely on high-volume, low-margin sales to stay open. But when PBMs change MAC lists or reduce dispensing fees, those margins vanish overnight.

At the same time, three PBMs - CVS Caremark, Express Scripts, and OptumRx - control 80% of the market. They set the rules. Independent pharmacies have little power to negotiate. Chain pharmacies have some leverage because they fill so many prescriptions. But independents? They’re at the mercy of MAC lists and contract terms they didn’t write.

What’s Changing in 2025?

The Federal Trade Commission is cracking down on spread pricing. In 2023, they launched investigations into how PBMs use opaque MAC lists to inflate reimbursement without transparency. The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 forced Medicare Part D to disclose drug pricing, and that pressure is starting to spill into commercial insurance.

Now, 15 states have created Prescription Drug Affordability Boards (PDABs). These boards can set Upper Payment Limits (UPLs) - the maximum amount payers can be charged for a drug. Some UPLs are set below current MAC rates, which forces PBMs to lower prices or lose reimbursement. That’s good for patients and payers. But it’s risky for pharmacies: if the UPL drops below what the pharmacy paid for the drug, they lose money on every fill.

Meanwhile, PBMs are pushing Generic Effectiveness Rates (GERs). These are contractual limits that cap how much a PBM will pay for generics over a year. If a pharmacy exceeds the GER, they get paid less. It’s a way for PBMs to control spending - but it also discourages pharmacies from dispensing even low-cost generics if they’ve already hit their limit.

Who Really Wins and Loses?

Let’s break it down:

- PBMs win - they profit from spread pricing and control the reimbursement rules.

- Insurers and Medicare win - they pay less overall, even if the system is opaque.

- Patients win on price - they pay low copays - but lose on transparency and sometimes on access if cheaper drugs aren’t available.

- Pharmacies lose - squeezed margins, unpredictable reimbursements, and no voice in the system.

- Manufacturers lose - generic drug makers face price pressure, but branded drug makers are losing market share fast.

The system was designed to save money. And it has - billions of dollars saved since the 1990s. But the savings aren’t going where they should. They’re going to corporate middlemen, not to patients or pharmacies. And the people who actually hand the medication to you - the pharmacist - are being pushed to the edge.

What Can Be Done?

Transparency is the first step. If MAC lists were published and standardized, pharmacies could plan better. If patients knew what drugs cost - not just their copay - they could ask for cheaper alternatives.

Some pharmacies are switching to direct primary care models or cash-based pricing for generics, bypassing PBMs entirely. A few states are experimenting with pharmacy reimbursement based on clinical outcomes, not just volume. That’s promising.

But until reimbursement models reward value - not volume - and until pharmacies have a seat at the table, the financial imbalance will keep growing. The goal should be simple: get patients the right drug, at the lowest cost, and make sure the pharmacy can stay open to deliver it.

Why do pharmacies prefer to dispense generic drugs?

Pharmacies prefer generics because they have much higher profit margins - around 42.7% on average - compared to just 3.5% for brand-name drugs. Even with low dispensing fees, the markup on generics makes them far more profitable per prescription. However, this only holds true if the reimbursement rate (MAC) is high enough to cover the cost and leave a margin. If the MAC drops below the pharmacy’s acquisition cost, they lose money on every generic filled.

What is a MAC list and how does it affect reimbursement?

A Maximum Allowable Cost (MAC) list is a pricing schedule used by pharmacies and payers to set the highest amount a pharmacy will be reimbursed for a generic drug. It’s not based on what the pharmacy paid, but on what the payer decides is “reasonable.” MAC lists vary widely between PBMs and states, with no national standard. If the MAC is set too low, pharmacies lose money. If it’s set too high, PBMs profit from the spread between what they pay the pharmacy and what they charge the insurer.

Do generic substitutions always save money?

Not always. While switching from a brand-name drug to its generic version saves money, switching between two generics in the same class often saves very little - especially if the PBM has placed a higher-priced generic on the formulary. Studies show some generic alternatives cost 20 times more than others in the same therapeutic class. The real savings come from replacing expensive brand-name drugs, not from swapping one generic for another.

How do PBMs profit from generic substitution?

PBMs profit through spread pricing: they negotiate a low price with the pharmacy (e.g., $1.50 per pill) but charge the insurer a higher amount (e.g., $7.00). The difference - $5.50 - is their profit. They maximize this spread by including higher-priced generics on MAC lists, even when cheaper, equally effective options exist. The pharmacy gets paid the MAC amount, so they don’t care which one is chosen - only that they get reimbursed.

Why are independent pharmacies closing?

Independent pharmacies are closing because reimbursement rates have stagnated while operating costs have risen. With dispensing fees stuck at $4-$6 and MAC lists frequently dropping below acquisition costs, many pharmacies earn less than $1 per generic prescription after expenses. With three PBMs controlling 80% of the market, independents have little bargaining power. Chain pharmacies survive by volume and corporate backing; independents often can’t compete.

Louis Llaine

December 8, 2025 AT 08:53So let me get this straight - pharmacists are basically paid to be glorified vending machines, and the real money’s being siphoned off by some corporate middlemen who don’t even touch the pills? Cool. Cool cool cool. I’ll just keep paying my $10 copay and pretending I’m saving money while the whole system laughs all the way to the bank.

Helen Maples

December 9, 2025 AT 02:12The structural flaws in this system are not accidental - they are by design. PBMs have consolidated power to extract profit from every layer of the supply chain while externalizing risk onto independent pharmacies and patients. The MAC list is a regulatory fiction: it appears to control costs, but in reality, it enables price manipulation under the guise of efficiency. Transparency mandates and UPLs are necessary first steps, but without breaking the PBM monopoly, reform will remain performative.

Jennifer Anderson

December 9, 2025 AT 03:14hey i just wanted to say i really appreciate you breaking this down - i work at a small pharmacy and this is our daily reality. we’re not greedy, we just want to be able to pay our rent and keep the lights on. sometimes we lose money on generics and still fill them because we know someone needs them. it’s not about profit anymore, it’s about survival. thank you for saying what we can’t always say out loud.

Kurt Russell

December 10, 2025 AT 13:18THIS IS THE MOST IMPORTANT POST I’VE READ ALL YEAR. 🚨

Pharmacies are the last line of defense between you and a deadly disease - and they’re being starved to death by corporate greed. Imagine if your firefighter got paid $1.50 per call while the city paid $500 to a middleman who never showed up. That’s this system. We need to demand transparency, support local pharmacies, and call out PBMs for what they are: financial parasites. This isn’t healthcare - it’s a rigged casino. Let’s change it.

Ryan Sullivan

December 12, 2025 AT 04:29The empirical evidence is unequivocal: the current reimbursement architecture exhibits profound misalignment between incentivized behavior and societal welfare. The Maximum Allowable Cost (MAC) mechanism functions as a pseudo-market distortionary tool, enabling spread pricing arbitrage that is both economically inefficient and ethically indefensible. The consolidation of Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) into an oligopolistic triad has created a negative externality wherein the cost of care is externalized onto independent providers. Until structural antitrust interventions occur - and reimbursement is decoupled from volume-based metrics - the system will continue to cannibalize its own infrastructure.

Sangram Lavte

December 13, 2025 AT 02:50Interesting read. In India, generics are cheap because the government controls pricing and manufacturers compete on volume. No middlemen. No MAC lists. Pharmacies make a small fixed margin, patients pay less, and everyone wins. Maybe the U.S. needs to stop letting Wall Street run healthcare and just regulate like other countries do.

Desmond Khoo

December 14, 2025 AT 06:13Man… I had no idea. 😢

Just got my blood pressure med filled today - paid $10, no big deal. But now I’m wondering if the pharmacy lost money on it. I’ll start asking my pharmacist what the real price is. Maybe I can help by choosing the cheapest one. Small steps, right? 💪

Sam Mathew Cheriyan

December 14, 2025 AT 11:33lol this is all just a psyop. the real reason generics are pushed is so the government can track you through your meds. they put microchips in the pills, and the PBMs are just front for the surveillance state. also, the FDA is owned by big pharma. ask yourself - why do they let you buy insulin for $4 but not your blood pressure med? coincidence? i think not.

Ernie Blevins

December 15, 2025 AT 06:18Pharmacies are losing money? Newsflash: they’re all overpriced and lazy. Just charge less. People will come. Stop blaming the system. If you can’t make it, close up. Simple.