8

How Paragraph IV Patent Challenges Speed Up Generic Drug Entry

When a brand-name drug’s patent is about to expire, the race to bring out a cheaper generic version begins - but it’s not just a matter of copying the formula. Behind every generic drug that hits the shelf is a complex legal battle called a Paragraph IV certification. This isn’t a loophole. It’s a carefully designed part of U.S. drug law that lets generic companies challenge weak patents and get to market faster - all while protecting innovation. Understanding how it works explains why some generics appear suddenly, why prices drop sharply, and why some drugs stay expensive for years longer than expected.

What Is Paragraph IV and Why Does It Exist?

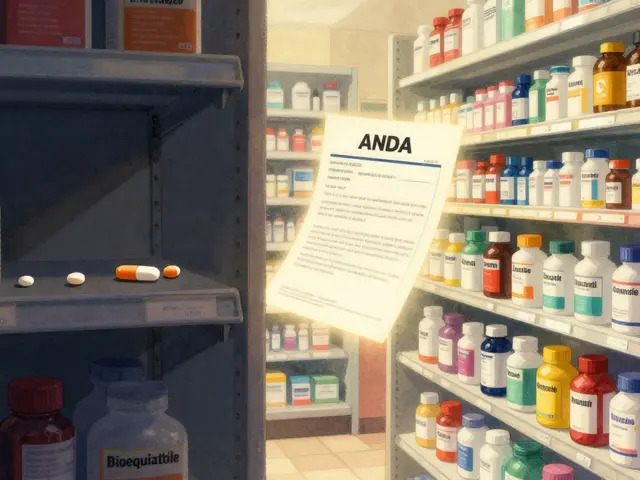

Paragraph IV isn’t a law itself. It’s a section of the Hatch-Waxman Act, passed in 1984 to fix a broken system. Before then, generic companies had to run full clinical trials to prove their drugs were safe and effective - even if they were exact copies of brand-name drugs. That made generics too expensive and slow to develop. At the same time, brand companies feared losing their monopoly too soon, which hurt their ability to recoup research costs. The Hatch-Waxman Act struck a balance. It let generic manufacturers file an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) - skipping most clinical trials - as long as they proved their product was bioequivalent. But here’s the catch: they had to address every patent listed for the drug in the FDA’s Orange Book. That’s where Paragraph IV comes in. If a generic company believes a patent is invalid, unenforceable, or won’t be infringed, they can file a Paragraph IV certification. This isn’t a request. It’s a legal challenge. And by filing it, they trigger a lawsuit from the brand company - even if no actual sale has happened yet. This is called an “artificial act of infringement.” It sounds strange, but it’s intentional. The law forces the issue into court so a judge can decide if the patent holds up - before the generic drug even hits the market.The Step-by-Step Process: From Filing to Market Entry

The process starts when a generic company picks a brand drug with expiring patents. They dig into the Orange Book - the FDA’s official list of approved drugs and their patents. Not all patents are equal. Composition-of-matter patents (covering the actual molecule) are strongest. But many brand companies list method-of-use patents (how the drug is taken), formulation patents (how it’s made), or even packaging patents. These are easier to challenge. If the generic company finds a patent they think is weak, they file their ANDA with a Paragraph IV certification. They must send a detailed letter to the brand company explaining why. This isn’t a bluff. It needs facts: prior art, technical analysis, legal arguments. If the letter is vague or incomplete, the FDA rejects it. Between 2018 and 2022, 63% of rejected Paragraph IV notices failed because the legal basis was too weak. Once the brand company gets that letter, they have exactly 45 days to sue. If they do, the FDA can’t approve the generic for 30 months - unless the court rules sooner. This is called the 30-month stay. It’s a big advantage for brand companies. It gives them time to fight in court while the generic sits on the sidelines. The real battle happens in federal court. Judges don’t just look at the drug. They look at the patent’s language. A key moment is the Markman hearing - where the judge defines what each patent claim actually means. If the judge says the patent covers a specific chemical form, but the generic uses a different one, the generic wins. If the judge says the patent covers a broad method, and the generic uses that same method, the brand wins. The outcome decides everything. If the generic wins, the FDA approves it immediately. If the brand wins, the generic waits until the patent expires.The 180-Day Exclusivity Prize

Here’s the kicker: the first generic company to file a successful Paragraph IV certification gets 180 days of exclusive market access. No other generic can enter during that time. That’s not just a reward - it’s a financial jackpot. During those six months, the first filer typically captures 70 to 80% of the entire generic market. For a blockbuster drug, that can mean billions in revenue. That’s why so many generic companies race to be first. In 2014, the FTC found that 87% of Paragraph IV filers were trying to be the first to file. But it’s risky. If you lose the lawsuit, you pay damages. In 2017, Mylan was ordered to pay $1.1 billion to Novartis for willful infringement after challenging Gleevec®’s patent. Many companies spend $2.3 million just preparing their case before they even file. And if they win, they need $15-25 million ready to scale up manufacturing overnight.

Why Some Challenges Succeed - And Others Don’t

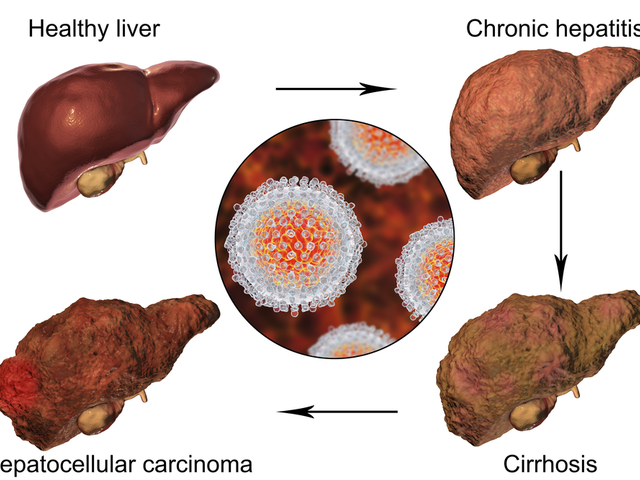

Success rates tell the real story. According to a 2021 UNC study of over 1,700 cases, Paragraph IV challenges succeed about 65% of the time. That’s higher than patent challenges at the USPTO, which only succeed 35% of the time. Why? Because federal courts use a lower standard: “preponderance of evidence.” The generic company just needs to show it’s more likely than not that the patent is invalid. At the USPTO, they need “clear and convincing evidence” - a much higher bar. Successful challenges often target patents that are obvious or based on old science. Teva’s 2019 win against Pfizer’s Lyrica® patent is a classic example. The patent covered a specific way to use the drug for nerve pain. Teva showed the method was already known in medical literature. The court agreed - and Lyrica generics flooded the market. But when brand companies pile on patents - especially secondary ones - it gets harder. AbbVie’s Humira® had over 100 patents listed in the Orange Book. Dozens of Paragraph IV challenges failed because courts upheld the formulation patents, even though the original molecule patent had expired. That’s called “patent thickets.” By 2020, the average drug had 4.8 patents listed - up from just 1.2 in 1984.Settlements, Delays, and the Pay-for-Delay Problem

Most Paragraph IV cases never go to trial. About 76% settle. And many of those settlements aren’t fair. In “pay-for-delay” deals, the brand company pays the generic company to stay off the market. Instead of letting competition lower prices, they split the profits. The FTC called it anti-competitive. In 2013, the Supreme Court ruled in FTC v. Actavis that these deals could violate antitrust laws - but they didn’t ban them. They just made them harder to defend. These delays cost consumers. When a generic finally enters after a successful Paragraph IV challenge, prices drop by an average of 79% within six months, according to a 2019 study by Professor Margaret Kyle. But when settlements delay entry by months or years, those savings vanish.

How This Compares to Other Countries

The U.S. system is unique. Europe doesn’t have a Paragraph IV equivalent. Generic companies there can’t challenge patents before approval. They have to wait until the patent expires - or get sued after launching. That means generic entry in Europe often takes 1-2 years longer than in the U.S. That’s why the U.S. leads in generic access. In 2021 alone, Paragraph IV challenges enabled 287 brand-name drugs to go generic - saving consumers $98.3 billion in potential spending. Between 2009 and 2019, the system saved U.S. consumers $1.68 trillion. But the system is under pressure. Brand companies are filing more patents later in a drug’s life. In 2023, 41% of new drug applications included patents filed in the final two years of the original patent term. That’s a tactic to stretch exclusivity beyond what Congress intended.What’s Changing Now?

The government is starting to push back. The 2023 CREATES Act makes it harder for brand companies to block generic manufacturers from getting samples needed for testing. The FDA’s 2022 rule on citizen petitions forces companies to be more transparent when they use regulatory delays to block generics. The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 lets Medicare negotiate drug prices - a move that could reduce the financial incentive for brand companies to fight generics so hard. And now, generic companies are combining Paragraph IV litigation with USPTO post-grant reviews. In 2022, there was a 47% jump in cases using both tools together. This gives them a two-pronged attack: challenge the patent in court and at the patent office. The FTC says reforming Paragraph IV to stop patent thickets is a top priority. Whether Congress acts remains to be seen. But one thing is clear: as long as patents are listed in the Orange Book, and as long as generics have the money and courage to challenge them, Paragraph IV will keep shaping how we get affordable medicine.Why This Matters to You

If you or someone you know takes a prescription drug, this system affects you. A Paragraph IV challenge could mean your $500 monthly pill drops to $20 - in a matter of months. It could mean a life-saving drug becomes accessible when it otherwise wouldn’t be. But it also means delays. If a brand company files 10 patents, and one holds up, your access is delayed - even if the rest are weak. That’s why transparency matters. You should know why a generic isn’t available. And you should know that behind every cheap drug on the shelf, there’s often a legal battle that changed the course of medicine.What is a Paragraph IV certification?

A Paragraph IV certification is a legal statement filed by a generic drug company with its Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA). It claims that one or more patents listed for the brand-name drug in the FDA’s Orange Book are invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed by the generic version. This triggers a patent lawsuit and is the legal pathway for generic drugs to enter the market before patent expiration.

How long does a Paragraph IV lawsuit take?

On average, Paragraph IV litigation lasts about 28.7 months, according to Federal Judicial Center data. The law allows for a 30-month regulatory stay, meaning the FDA can’t approve the generic during that time unless the court rules earlier. Many cases settle before trial, which can shorten the timeline.

Why do generic companies risk filing a Paragraph IV challenge?

The first company to successfully file a Paragraph IV certification gets 180 days of exclusive market rights - no other generic can enter during that time. That exclusivity often leads to massive profits, sometimes billions of dollars, making the high legal costs and risk worthwhile. Losing, however, can mean paying hundreds of millions in damages.

What’s the difference between Paragraph IV and IPR?

Paragraph IV challenges happen in federal district court and use a lower burden of proof (preponderance of evidence). Inter Partes Review (IPR) happens at the USPTO and requires clear and convincing evidence. Paragraph IV is more expensive - averaging $7.8 million per case - but has a higher success rate (65%) compared to IPR (35%).

Can brand companies delay generic entry without litigation?

Yes. Brand companies sometimes file multiple patents late in a drug’s life to create patent thickets. They may also delay generic access by refusing to provide drug samples needed for testing, or by filing citizen petitions with the FDA to block approval. The CREATES Act and FDA rules now limit some of these tactics.

How much do generic drugs save consumers?

Between 2009 and 2019, generic drugs entering the market through Paragraph IV challenges saved U.S. consumers $1.68 trillion. When a generic enters after a successful challenge, prices typically drop by 79% within six months.

RAJAT KD

January 9, 2026 AT 01:11Paragraph IV is the only thing keeping insulin from costing $10 a vial. Stop pretending this is just legal theater-it’s life or death for millions.

Darren McGuff

January 10, 2026 AT 05:56Let me break this down for you folks who think this is just corporate chess. The 180-day exclusivity window? That’s not a reward-it’s a market distortion. It creates a race to the bottom where companies spend millions just to be first, not to innovate. And guess who pays? You do, in higher prices during those six months because there’s zero competition. The system’s rigged to reward speed over substance.

Meanwhile, in Europe, generics enter slower but more evenly. No one gets a monopoly windfall. Prices drop steadily. The U.S. system isn’t better-it’s just louder.

And don’t get me started on pay-for-delay. If you’re a brand company paying a generic to sit out, you’re not protecting innovation-you’re buying silence. The FTC’s been screaming about this since 2010, and Congress still hasn’t fixed it.

Bottom line: we need to cap exclusivity at 90 days, ban settlements that delay entry, and force patent transparency. This isn’t rocket science. It’s just politics.

Aron Veldhuizen

January 11, 2026 AT 22:19You all miss the fundamental philosophical flaw: Paragraph IV assumes that patents are binary-valid or invalid. But patents aren’t facts. They’re social constructs, legal fictions engineered to incentivize investment. The entire system is predicated on the illusion that innovation can be quantified, measured, and monetized in discrete units called ‘claims.’

When a generic company files a Paragraph IV challenge, they’re not challenging a patent-they’re challenging the legitimacy of the entire capitalist framework that assigns ownership to ideas. And yet, they do it using the very tools of that system: litigation, money, and procedural manipulation.

This isn’t about drugs. It’s about whether we believe ideas can be owned. And if they can, who gets to decide? The courts? The FDA? The shareholders? The answer is: nobody. And that’s why this system will always be broken.

Phil Kemling

January 12, 2026 AT 03:01It’s funny how we celebrate Paragraph IV as a win for consumers, but never ask why the system requires a $2.3 million legal gamble just to get a $20 pill. We’ve turned access to medicine into a high-stakes poker game. And the house always wins-unless you’re lucky enough to be the first to call.

What’s the moral here? That if you’re poor, you wait. If you’re rich and litigious, you win. That’s not innovation. That’s exploitation dressed up as competition.

Chris Kauwe

January 12, 2026 AT 18:32Let’s not sugarcoat this: Paragraph IV is the ultimate regulatory arbitrage. Generic manufacturers exploit the preponderance-of-evidence standard in district court to dismantle patents that would never survive IPR at the USPTO. It’s a two-tiered system where the same patent gets different treatment based on venue. That’s not justice-it’s forum shopping on a national scale.

And the 180-day exclusivity? That’s a cartel mechanism disguised as market incentive. The FTC should be investigating these filers for collusion, not patting them on the back.

Meanwhile, brand companies respond by filing 100 patents on a single drug. That’s not innovation-it’s legal obstructionism. We need a cap on Orange Book listings. One molecule, one patent. Done.

Jeffrey Hu

January 13, 2026 AT 07:53Everyone’s missing the real issue: the 30-month stay isn’t a delay-it’s a loophole. The law says the FDA can’t approve until the patent issue is resolved, but what if the patent is obviously garbage? The court can rule in 6 months, but the stay still runs for 30. That’s not fairness. That’s bureaucratic inertia.

And the settlement rate? 76%? That’s because brand companies know they’re weak. They’d rather pay off the generic than risk a public loss. It’s not about the money-it’s about reputation. No pharma exec wants to be the one who lost a patent in open court.

Also, the CREATES Act? Good, but it’s a Band-Aid. We need to eliminate the 30-month stay entirely and replace it with a 12-month expedited review. Simple. Effective.

Drew Pearlman

January 13, 2026 AT 20:02Can I just say how proud I am of the system? Seriously. We’ve built a mechanism where a single legal filing can bring down a $500-a-month drug to $20-and that’s not magic, that’s policy. It’s the rare case where capitalism, law, and public health actually align.

Yes, there are abuses. Yes, there are delays. But look at the numbers: $1.68 trillion saved in a decade. That’s more than the GDP of most countries. That’s not a flaw-it’s a triumph.

And the fact that generic companies are now combining Paragraph IV with IPR? That’s innovation in action. They’re not just playing the game-they’re upgrading the rules.

Let’s not fix what isn’t broken. We need more of this, not less. More courage. More filing. More lawsuits. More generics. More savings. More lives saved.

Keep fighting. Keep challenging. The system works-when we use it.

Catherine Scutt

January 15, 2026 AT 18:16Ugh, I read this whole thing and now I’m mad. Why does it take a lawsuit for me to get my blood pressure med for $10? My grandma’s on 7 meds. Half of them are still $400 because some lawyer in NYC decided to file a patent on the color of the pill.

It’s not fair. It’s not right. And it’s not complicated-it’s greedy.

Pooja Kumari

January 16, 2026 AT 02:05Every time I think about this, I cry. Not because I’m emotional-I’m just tired. My brother died because he couldn’t afford his chemo drug. It was off-patent in 2018. But because of a stupid formulation patent, generics didn’t come until 2022. Four years. Four years of him paying $8,000 a month while the company made $2 billion.

They call it innovation. I call it murder with a patent.

I don’t care about the legal jargon. I don’t care about the 180-day exclusivity. I care that my brother is gone because someone decided a pill’s coating was worth a monopoly.

Who’s going to fix this? Not Congress. Not the FDA. Not the courts. They’re all paid by the same people who profit from this.

So I’m just here. Waiting. For the next family to lose someone because they couldn’t afford a pill.

Lindsey Wellmann

January 16, 2026 AT 02:36OK BUT LIKE 😭 WHY IS THIS NOT ON THE NEWS?!?! This is literally the most important thing happening in American healthcare and no one’s talking about it!! 🤯

Like imagine if your Netflix subscription suddenly dropped from $20 to $3 because someone sued the company… but you had to pay $2 million to file the lawsuit first? 😳

Also, I just Googled ‘Paragraph IV’ and now I’m crying into my oat milk latte. This is the most dramatic legal thriller I’ve ever read. Netflix, make a series. I’ll binge it. 🍿💔

Elisha Muwanga

January 16, 2026 AT 14:26Let’s be clear: this Paragraph IV nonsense is a gift to foreign generic manufacturers who exploit American law to undercut our domestic pharmaceutical industry. We built this system to reward innovation, not to hand our crown jewels to overseas corporations who don’t even pay U.S. taxes.

Meanwhile, American scientists and engineers who developed these drugs are being sidelined while Chinese and Indian firms cash in on our legal loopholes. This isn’t consumer protection-it’s economic surrender.

And don’t get me started on the FTC. They’re more interested in breaking up tech companies than protecting American medical sovereignty.

We need a new law: only U.S.-based companies can file Paragraph IV certifications. No exceptions. National security. Economic patriotism. It’s time we stopped outsourcing our health to foreign litigants.