7

Delayed Drug Reactions: What Happens Days to Weeks After Taking a Medication

Most people expect side effects from medications to show up quickly-maybe within hours, or at most a day or two. But what if your rash doesn’t appear until day 10? Or your fever spikes on day 21, long after you finished the antibiotic? These aren’t random bad luck events. They’re delayed drug reactions, a hidden but dangerous side of medicine that doctors often miss-and patients rarely recognize until it’s too late.

Why Do Some Reactions Take Weeks to Show Up?

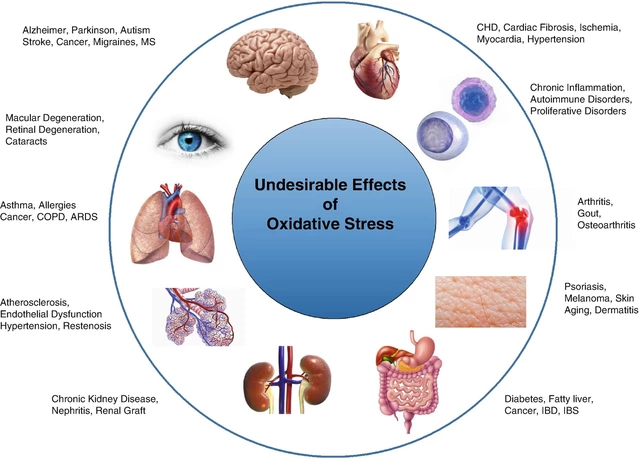

Unlike immediate allergic reactions (like hives or anaphylaxis), delayed drug reactions aren’t caused by IgE antibodies. They’re driven by your immune system’s T-cells, which take time to recognize the drug as a threat. Think of it like a slow-burning fuse. The drug enters your body, gets processed, and your immune system starts building a response. It can take 5 to 8 weeks for that response to become visible on your skin, in your organs, or in your blood tests.

This delay is why so many people are misdiagnosed. A rash that appears after 10 days? Doctors often think it’s a virus-like measles or roseola. A fever and swollen glands after 3 weeks? Maybe it’s mononucleosis. But if you started a new medication 2 weeks ago, it’s likely not a virus at all. It’s your immune system attacking your own tissue because of the drug.

Common Types of Delayed Reactions

Not all delayed reactions are the same. They range from annoying to life-threatening. Here are the main types:

- Maculopapular exanthema (MPE): This is the most common. It looks like a flat, red rash with small raised bumps. It usually shows up 5 to 14 days after starting the drug. Often mistaken for a viral rash, it’s harmless in most cases-but it can be the first sign of something worse.

- Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (DRESS): This one’s serious. It involves fever over 38.5°C, swollen lymph nodes, high levels of eosinophils (a type of white blood cell), and damage to internal organs like the liver or kidneys. Onset is typically 2 to 8 weeks after starting the drug. About 8% of people with DRESS die from it. Survivors often deal with long-term organ damage or autoimmune diseases.

- Stevens-Johnson Syndrome (SJS) and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis (TEN): These are medical emergencies. The top layer of your skin starts dying and peeling off, like a severe burn. SJS affects less than 10% of your body; TEN affects more than 30%. Onset is usually 1 to 4 weeks after taking the drug. Mortality rates hit 5-10% for SJS and jump to over 30% for TEN if more than half your skin is affected.

- Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis (AGEP): This one shows up fast after the delay-suddenly covered in tiny, sterile pustules. It usually resolves within 15 days after stopping the drug, but it’s terrifying while it lasts. Often triggered by antibiotics like sulfonamides.

Which Medications Cause These Reactions?

Some drugs are far more likely to trigger delayed reactions than others. The biggest culprits:

- Anticonvulsants: Carbamazepine, phenytoin, lamotrigine. These are the most dangerous. Lamotrigine, used for epilepsy and bipolar disorder, causes DRESS in 1 in 1,000 users. Carbamazepine triggers SJS in people with the HLA-B*15:02 gene-common in Southeast Asia, rare in Europe.

- Antibiotics: Especially sulfonamides (like sulfamethoxazole), penicillins, and cephalosporins. Reactions usually show up within 2 weeks.

- Allopurinol: Used for gout. Causes DRESS and SJS, especially in people with the HLA-B*58:01 gene. Screening for this gene before prescribing can prevent up to 80% of severe reactions.

- NSAIDs: Ibuprofen, naproxen. Less common, but still responsible for 18% of all delayed reactions.

Here’s the catch: you might have taken the drug for weeks without issue. Then, out of nowhere, your body flips. That’s because T-cells need repeated exposure to build up their response. The first time you took it? No problem. The 14th time? Your immune system finally says, “Enough.”

Genetics Play a Huge Role

Why do some people react and others don’t? Genetics. Certain HLA genes make your immune system more likely to misfire.

- HLA-B*15:02 → Carbamazepine → SJS in people of Han Chinese, Thai, Malaysian descent.

- HLA-B*58:01 → Allopurinol → DRESS and SJS in Southeast Asians.

- HLA-A*31:01 → Oxcarbazepine → DRESS in European and Japanese populations.

In Thailand, doctors test for HLA-B*15:02 before prescribing carbamazepine. In Taiwan, screening for HLA-B*58:01 before allopurinol has cut severe reactions by 90%. In the U.S. and Australia, this isn’t routine-yet. But if you’re of Asian descent and need one of these drugs, ask your doctor about genetic testing. It’s cheap, simple, and could save your life.

How Are These Reactions Diagnosed?

There’s no single blood test. Diagnosis relies on three things:

- Timing: Did the reaction start 5-8 weeks after starting the drug?

- Symptoms: Does it match RegiSCAR criteria (for DRESS, SJS, etc.)?

- Exclusion: Could it be an infection, autoimmune disease, or cancer?

Doctors use scoring systems like the Naranjo scale. A score of 6 or higher means the reaction is “probable.” But even then, it’s easy to miss. One study found 32% of early DRESS cases were wrongly diagnosed as viral infections. That delay can be deadly.

Specialized tests exist but aren’t widely used:

- Lymphocyte Transformation Test (LTT): Checks if your T-cells react to the drug in a lab dish. 75-85% accurate.

- Patch testing: Applied to the skin. Only 40-60% accurate, but useful for some drugs.

- TCRβ sequencing: New technique that tracks the exact immune cells involved. 92% accurate for carbamazepine-SJS. Still experimental.

Drug rechallenge-taking the drug again to see if the reaction returns-is the gold standard. But it’s banned for SJS, TEN, and DRESS because the risk of death is too high.

What Happens If You Don’t Stop the Drug?

Delaying discontinuation is the #1 mistake. If you keep taking the drug after the first signs of a reaction, mortality risk jumps by 35%. That’s not a small number. In DRESS, continuing the drug can turn mild liver inflammation into liver failure. In SJS, it can turn 5% skin loss into 50%.

One Reddit user, u/ChronicRashSurvivor, described taking lamotrigine for 22 days before the fever hit. By day 28, their liver enzymes were over 1,200 U/L. They didn’t stop the drug until day 30. Recovery took five months.

Another patient, AllergyWarrior87, had AGEP from sulfamethoxazole. They stopped the drug on day 10 and saw pustules vanish in 12 days. But the hyperpigmentation? Still there six months later.

Stopping the drug within 48 hours of symptom onset is the single most important step. No exceptions.

Treatment: What Works and What Doesn’t

There’s no magic cure. Treatment is about stopping the damage and supporting your body.

- Stop the drug immediately: Non-negotiable.

- Corticosteroids: Prednisone at 0.5-1 mg/kg per day for 2-4 weeks, then slowly tapered. Works for DRESS and severe MPE. But steroids don’t help SJS/TEN as much.

- Cyclosporine: Used in Japan for DRESS with kidney involvement. Shows 50% faster recovery than steroids alone.

- IVIG: Intravenous immunoglobulin. Used in SJS/TEN to block immune attacks. Controversial, but often tried.

- Supportive care: Fluids, wound care, pain control, monitoring organ function. In severe cases, patients need ICU-level care.

Antibiotics? Usually not needed. These are immune reactions, not infections. Giving antibiotics can make things worse by adding more drugs your body has to process.

Long-Term Effects: The Hidden Cost

Even if you survive, the damage doesn’t always go away.

- 35% of SJS/TEN survivors develop chronic eye problems-dryness, scarring, even blindness.

- 22% develop autoimmune diseases like lupus or thyroiditis within two years.

- 42% of DRESS patients have lasting liver damage.

- Many report ongoing fatigue, anxiety, and fear of all medications.

One European study found DRESS patients lost 23% of their work productivity for six months after recovery. That’s not just medical-it’s financial, emotional, and social.

What Should You Do If You Suspect a Delayed Reaction?

If you’ve taken a new medication and develop any of these after 5 days:

- Fever that won’t break

- Widespread rash, blisters, or peeling skin

- Swollen lymph nodes

- Unexplained fatigue or nausea

- Yellow skin or dark urine (liver issues)

Stop the drug immediately. Call your doctor. Don’t wait. Don’t assume it’s “just a virus.” Bring a list of all medications you’ve taken in the last 8 weeks. Ask: “Could this be a delayed drug reaction?”

If you’re of Asian descent and prescribed carbamazepine, allopurinol, or oxcarbazepine, ask about HLA genetic testing before starting. It’s a simple blood test. It costs less than $100. It could prevent a death sentence.

The Future: Prevention Is Possible

Science is catching up. The FDA now recommends HLA-B*58:01 screening before allopurinol in Asian patients. Taiwan’s national program has cut DRESS cases by 80%. AI systems are being trained to flag high-risk drug-gene combinations in electronic health records. Organ-on-chip models are being built to test drug reactions without hurting patients.

But until these tools are widespread, you’re your own best defense. Know the signs. Know your meds. Speak up. A rash that shows up after two weeks isn’t normal. It’s a warning.

christy lianto

January 8, 2026 AT 00:59This post is a wake-up call. I took lamotrigine for six months before a rash hit on day 42. My doctor called it ‘heat rash.’ I nearly died. Stop ignoring delayed reactions - they’re not glitches, they’re warnings.

Luke Crump

January 8, 2026 AT 21:07So let me get this straight - your immune system is like a disgruntled employee who finally files a complaint after 14 weeks of unpaid overtime? And the drug is the boss who didn’t notice? That’s poetic. Also terrifying. We’ve turned medicine into a passive-aggressive relationship.

Lois Li

January 9, 2026 AT 17:54Thank you for writing this. I’m a nurse and I’ve seen too many patients dismissed because their rash showed up ‘too late.’ It’s not just about genetics - it’s about systemic ignorance. We need better training for primary care docs. And we need patients to trust their guts. If something feels wrong after a new med, speak up - even if it’s been weeks.

Manish Kumar

January 11, 2026 AT 14:42Let me tell you something - in India, we don’t have the luxury of HLA testing for everything. My uncle took allopurinol for gout and got DRESS. He survived, but lost his kidney. The doctor said, ‘It’s rare.’ But rare doesn’t mean impossible. We need awareness at the village level, not just in fancy hospitals in Mumbai. If you’re on these meds, watch your skin, your fever, your pee color. Don’t wait for a lab report. Your body talks - you just have to listen.

And no, antibiotics won’t fix it. That’s like pouring gasoline on a fire because you think it’s cold.

Prakash Sharma

January 13, 2026 AT 04:18Why does America still ignore genetic screening? We test for everything else - why not this? In India, we don’t even have access to this info, but at least we don’t pretend it’s not real. You people act like medicine is a magic trick. It’s biology. And biology doesn’t care about your insurance plan.

Donny Airlangga

January 13, 2026 AT 15:15I had AGEP from sulfamethoxazole. Took me 10 days to realize it wasn’t a bug - I’d just started the antibiotic. Stopped it right away. Pustules vanished in 9 days. But the dark spots? Still there. My dermatologist said it’s permanent. So yeah - stop the drug fast. But also know: even if you survive, you’re not the same.

Kristina Felixita

January 14, 2026 AT 19:26OMG this is so important!! I just started carbamazepine last month and now I have this weird red patch on my chest… I’m gonna call my doctor tomorrow!! I didn’t even know this was a thing!! Please everyone - if you’re on any of these meds and feel off - don’t wait!! I’m sharing this with my whole family!!

Joanna Brancewicz

January 15, 2026 AT 20:05T-cell-mediated delayed hypersensitivity. HLA haplotype risk stratification. RegiSCAR criteria. Naranjo scale. LTT sensitivity 75-85%. Stop the drug within 48h. Steroids taper. IVIG controversial. Long-term autoimmune risk 22%. Don’t confuse with viral exanthem.

Evan Smith

January 17, 2026 AT 19:11So… you’re telling me my body is like a Netflix algorithm - ignores you for weeks, then suddenly recommends a full-on skin meltdown? And the only way to stop it is to unplug the whole system? I mean… kinda makes sense. Also terrifying. Can we get a ‘Don’t Die From This’ sticker for all prescriptions?

Ken Porter

January 19, 2026 AT 10:47Another American medical drama. In real countries, they screen before prescribing. Here? We wait until you’re peeling like a banana and then bill you $20k for ICU. Fix the system. Not the symptoms.